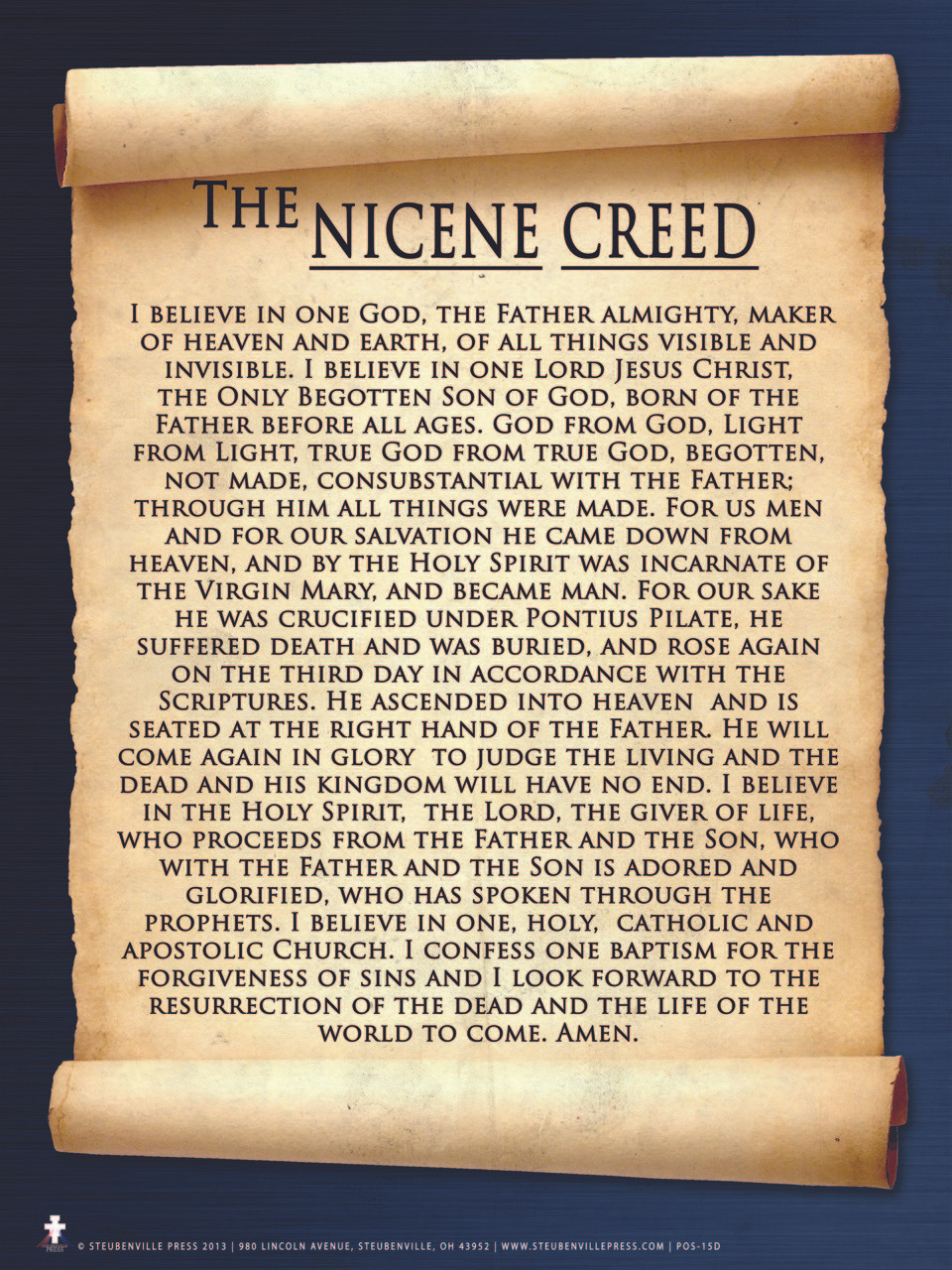

The Nicene Creed is held as the standard of Orthodoxy since the year 325. Those that have come to reject it have been considered heretics. We’ll discuss the various arguments used to defend the idea the Son is eternally begotten of the Father.

1. Historical argument:

This argument goes along the lines about the historical significance of the Creed. It has been used as the test case for orthodox trinitarian dogma for almost 2,000 years. It must be true because of such. That is a terrible argument. It is just when Protestants are pretending Catholics. It simply is a denial of sola Scriptura. The Canon of Nicea becomes the 67th book of the canon.

The more ironic issues are that usually the person presenting this objection is holding to the later Catholics’ addition of the Filioque clause of 1054. They are presenting a self-refuting position. We should accept the most historical trinitarian model and yet they accept a later version. Furthermore, they forget that the creed is debated in its own time. The old Niceans, New Niceans, Semi-Arians, and Radical Arians arouse in the aftermath of 325. Another debate is whether the patristics thought the Son and the Father share the numerically same essence or a generic essence. I also suppose that they would reject the Nicene statement on baptism.

2. Exegetical argument:

Some look at the phrase of the only-begotten son(John 1:14, 16, 18; 3:18; 1 John 4:9; Heb. 1:5) and think this is like it’s more common usage of when a Son is begotten of his Father. The sexual understanding is a Son gets his essence from his Father. So, the use in John and elsewhere is that it means Christ is derivative or originate from the Father that is underivative and unoriginate.

The argument’s strengths are its’ greatest weaknesses. It’s able to stress the usual and common meaning of “Begotten” and “Sonship” as it is a biological relation. The issue is that is what undermines it on its own terms. It is common that when a human is being begotten a mother is involved. So, if taken wooden literally you end up with a Quaternity. Further, the common idea in begetting leads to Semi-Arianism. When a person begets another they are begetting an entirely different being. Son’s don’t share a numerically same essence as their Fathers. So, even the more simple-minded proponent of eternal generation doesn’t end up taking the phrase in the ordinary way they were arguing it was supposed to be taken in the original argument. They end up realizing the more metaphorical meaning as it should be understood because God is not a man and the persons of the Trinity aren’t standing in biological relations to one another. So, what is the metaphor trying to get across? Some think it is meant to intend that the Son is derivative of the Father. I think the scope of the metaphor is found in a similar place to the primogeniture.

Waldron is tacitly assuming that “sonship” language is synonymous with “generation” language. But that’s naïve. We’re dealing with idiomatic categories. You can’t infer one idiom from another. Both categories can have different connotations, different literary allusions. For instance, you have to consider what OT texts lie behind the respective categories. Each category may be part of a separate literary chain or theological motif, with its own canonical history. Two independent streams that eventually converge in the NT.

For instance, Waldron doesn’t consider the possibility that the “only-begotten” metaphor is intended to evoke associations with primogeniture. Cf. BDAG 658a(2). The rights of the firstborn. That is then applied figuratively to Christ as the royal heir. In that case, the point of the metaphor is not derivation, but prerogatives.

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2011/10/whos-tampering-with-trinity.html

For further discussion on the issue of Sonship and for the argument from “only-begotten”, look here:

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2012/12/the-eternal-sonship-of-christ.html

The term for only-begotten is monogenes and it is debated to what it should be translated and that is because it has two plausible translations “one and only” or “only begotten”. This plays into a possible trinitarian apologetic against Unitarianism and into the debate about the doctrine of eternal generation:

E. Combining both answers, Jn 1:18 calls the Son the “one and only” God. If anything, a monogenes theos (Jn 1:18) sounds even more exclusive than a merely monos theos (Jn 17:3). Not just “one God”, but a “one of a kind” God. In a class by himself.

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2019/01/whos-only-true-god.html

This is also accepted by many Old Testament scholars such as Dr. Michael Heiser that possibly leans weight to the possibility that John is calling back to Old Testament themes of the uniqueness of God compared to anything else.

If there are other divine sons of God, what do we make of the description of Jesus as the “only begotten” son of God (John 1:14, 18; 3:16, 18; 1 John 4:9)? How could Jesus be the only divine son when there were others? “Only begotten” is an unfortunately confusing translation, especially to modern ears. Not only does the translation “only begotten” seem to contradict the obvious statements in the Old Testament about other sons of God, it implies that there was a time when the Son did not exist—that he had a beginning. The Greek word translated by this phrase is monogenes. It doesn’t mean “only begotten” in some sort of “birthing” sense. The confusion extends from an old misunderstanding of the root of the Greek word. For years monogenes was thought to have derived from two Greek terms, monos (“only”) and gennao (“to beget, bear”). Greek scholars later discovered that the second part of the word monogenes does not come from the Greek verb gennao, but rather from the noun genos (“class, kind”). The term literally means “one of a kind” or “unique” without connotation of created origin. Consequently, since Jesus is indeed identified with Yahweh and is therefore, with Yahweh, unique among the elohim that serve God, the term monogenes does not contradict the Old Testament language. The validity of this understanding is borne out by the New Testament itself. In Hebrews 11:17, Isaac is called Abraham’s monogenes. If you know your Old Testament you know that Isaac was not the “only begotten” son of Abraham. Abraham had earlier fathered Ishmael (cf. Gen 16:15; 21:3). The term must mean that Isaac was Abraham’s unique son, for he was the son of the covenant promises. Isaac’s genealogical line would be the one through which Messiah would come. Just as Yahweh is an elohim, and no other elohim are Yahweh, so Jesus is the unique Son, and no other sons of God are like him.

Michael S. Heiser. The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible (Kindle Locations 541-557). Lexham Press. Kindle Edition.

The case for it being “only-begotten” suffers from the weakness of being an argument from the etymology of the word. The focus of interpretation is not so much etymology but rather the contemporary usage of the term. It seems clear that it has been used to mean more than just “only-begotten” as the example from Hebrews 11:17 above shows. Robert Letham argues that monogenēs in its contexts in John as linked to the new birth of Christians. Whether that is the case can be debated but that still leaves us the issue of figuring out what “only-begotten” means. It still wouldn’t be a given that it means that the Son is eternally generated. It is a metaphor and itself could just be a biological metaphor for being unique.

Some note the use that the Father is often referred to as God and the Son is either referred to as “The Word”, “Lord”, “Son of God”, or the “Son of man”. So, from that, we may conclude that the Father holds a special and privileged place in the Trinity as the Monarch to which he passes being and divinity to the other members.

I think the argument suffers from a few flaws. The titles given to Jesus infer nothing about him having a derivative essence. They just state that he is as God as the Father. Further, the titles are just used to distinguish the Father from the Son. That isn’t meant to imply anything about the Father being unoriginate. It is merely used to distinguish the persons. God is often used as a proper noun to denote or refer to the Father, but that is because the Son and Spirit are also God.

A major prooftext for eternal generation is John 5:26:

For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself.

The common assumption is to think that life here refers to the Divinity of the Son or his eternal existence. That has no exegetical basis and simply reading Nicene Orthodoxy back into the text. In the passage, you have Christ giving that same life to believers in verse 5:21-22 and 6:57. So, the verse would result in pantheism if interpreted that way. Furthermore, the “life” spoken about is eschatological life. These statements are made in reference to the future resurrection.

The emphasis that the Father has granted the Son to have life in himself, and has given him authority to exercise judgement functions as a further response to the charge of v. 18 that Jesus was making himself equal to God. Because of his relation to the Father, like the Father, Jesus himself is the possessor and giver of life.

Lincoln, A. T. (2005). The Gospel according to Saint John (p. 204). London: Continuum.

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2010/02/life-of-world.html

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2011/06/life-in-himself.html

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2009/12/life-in-son.html

Some try to reframe the argument in terms that it seems in two areas. They will mention that the Father’s life is divine life. This seems to imply that it goes back prior to the events of the incarnation. The issue is that the non-eternal generation interpretation needs to explain the meaning that the Father has life in himself. I think a plausible understanding is that God can only give what he has. God is the “living God” and possesses immortality (John 6:57, 1 Tim. 6:16). While I believe this is true in the creator/creature distinction, the point is since God has this in and of himself(having not received it) he, therefore, can give it (John 1). The Son does what he sees the Father does. This isn’t the task of a creature. Only God gives life and can take it, but Christ shares in this divine prerogative. This shows why we have to honor the Son just as we honor the Father.

The other argument in regards to this is that this life is given to the Son. But the Son isn’t resurrected yet and therefore this life can’t refer to the Son qua his humanity, but rather his divinity. The problem with this understanding is that contextually this is what life means throughout the entire Johannine literature. That is even in this context you have a discussion about the Son being granted the authority to judge in the eschaton. So, it is even harder to believe this is an exception. The argument also fails to account for the fact that this “Eternal life” is actually possessed by believers now (verse 23-24 of the same chapter explains this). For more on this:

http://spirited-tech.com/Council/index.php/2018/12/11/this-is-eternal-life/

Another prooftext is Proverbs 8:22-26

“The Lord possessed me at the beginning of his work,

the first of his acts of old.

23 Ages ago I was set up,

at the first, before the beginning of the earth.

24 When there were no depths I was brought forth,

when there were no springs abounding with water.

25 Before the mountains had been shaped,

before the hills, I was brought forth,

26 before he had made the earth with its fields,

or the first of the dust of the world.

Some think that Proverbs provides the background for NT Christology. There are various reasons for that and the most common idea is that in the back of various NT authors’ minds are the idea that is related to Philo’s logos. For example, John calls Jesus the “Logos” but what does that title suppose to convey to the reader?

I can’t leave out a nonexistent allusion. There is no allusion to Prov 8 in Jn 1. There are many problems with that alleged comparison: Jn 1 is a historical narrative, Prov 8 is a poetic allegory. Lady Wisdom in Prov 8 is a fictional character who parallels Lady Folly in Prov 9. As Bruce Waltke explains in his commentary, Lady Wisdom is a metaphor for Solomon’s proverbial wisdom. Lady Wisdom is an observer, not a creator–unlike the Logos in Jn 1. Lady Wisdom is God’s first creature, whereas the Logos is the Creator. Lady Wisdom is on the creaturely side of the categorical divide whereas the Logos is on the divine side of the categorical divide. Jn 1 doesn’t use wisdom terminology. It calls the filial Creator logos rather than Sophia.

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2015/11/and-word-was-god.html

That isn’t the tip of the iceberg on the issue of Wisdom Christology in the NT. But that discussion is beyond the purpose of this article.

Here is another explanation for why Jesus is called the Word:

http://spirited-tech.com/Council/index.php/2018/02/20/why-is-jesus-called-the-word/

Another prooftext is Revelation 3:14

“And to the angel of the church in Laodicea write: ‘The words of the Amen, the faithful and true witness, the beginning of God’s creation.

I’ve already posted an article on this issue before:

http://spirited-tech.com/Council/index.php/2018/01/18/beginning-of-the-creation/

The other kind of argument for it is that we see the Son in his economic role acting inferior to the Father. The economic Trinity is revealing something about the ontological Trinity. That being the Father is the Monarch that passes or gives the Son his eternal essence/Divinity.

I simply don’t think we can make such inference from economic roles and that in practice we don’t. Suppose we looked at Philippians 2:9-11

9 Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, 10 so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

We have this speaking about Christ-exaltation. But the text is often used by Unitarians to defend the idea that Christ wasn’t God by nature. That the expectation is for us to infer he isn’t divine. The proponent of the argument above would be in a difficult place to deny such inferences. Second, we know that Christ could act in such roles that necessarily imply inferiority. Suppose the boss comes to work early before his secretary. The phone on her desk starts to ring and he answers it. He is acting inferior to his actual status as the boss but he isn’t now magically not the boss, but he functions as the secretary. Hays talks about Andreas Köstenberger’s case for Eternal generation via Agustianian inference here:

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2009/12/life-in-son.html

Another prooftext is Psalm 2:7

“I will surely tell of the decree of the Lord:

He said to Me, ‘You are My Son,

Today I have begotten You.

The proponent of eternal generation constantly thinks that the term “begotten” must refer to eternal generation. The issue is the text itself is about a Davidic king and has messianic overtones. It says “Today” and not timelessly begotten you. This is about Christ’s exaltation and has nothing to do with eternal generation.

The “decree” of the Lord determines his relationship to the king and to the nations. The Davidic king is by birth and by promise the “son of God.” Here it signifies a legal right (so TWOT 2: 316-17). His commission is to make “the domain of Yahweh visible on earth” (Zimmerli, 92: see Helmer Ringgren, “Psalm 2 and Belit’s Oracle for Ashurbanipal,” in The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth, ed. Carol F. Meyers and M. O’Connor [Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1983], 91-95). God is the Davidic king’s “father” (cf. 2Sa 7: 14; also cf. Ps 89: 27). In actuality, this relationship is confirmed at the moment of the coronation: “Today I have become your Father”; therefore, the theocratic king must respond to the interests and desires of his father and represent the will of God to his people. Jesus is the Christ, the “Son” of God, by the Father’s proclamation (Mt 3: 17; Mk 1: 11; Lk 3: 22). He is seated at the right hand of the Father (Ac 2: 33; Heb 1: 3), the place of kingly rule and authority.

VanGemeren, Willem A.. Psalms (The Expositor’s Bible Commentary) (Kindle Locations 4727-4734). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

Even proponents of eternal generation like Dr. Vern Poythress note that text attribute this text to moments that occur after the resurrection:

But since David is a type of the coming Messiah, the text is also pointing forward. Acts 13: 33 applies it to the resurrection and enthronement of Christ. Hebrews 5: 5 applies it to Christ’s being appointed High Priest, which may again have in mind his enthronement at the right hand of God.

Poythress, Vern S.. Knowing and the Trinity: How Perspectives in Human Knowledge Imitate the Trinity (Kindle Locations 3398-3399). P&R Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Another prooftext is Micah 5:2

2 But you, O Bethlehem Ephrathah,

who are too little to be among the clans of Judah,

from you shall come forth for me

one who is to be ruler in Israel,

whose coming forth is from of old,

from ancient days.

The issue with this prooftext is that it is stating that the Messiah comes from Eternity past.

The terms “old” (qedem; GK 7710) and “ancient times” (mîmê ʿôlām) may denote “great antiquity” as well as “eternity” in the strictest sense. The context must determine the expanse of time indicated by the expressions. In Micah 7: 14, for example, mîmê ʿôlām is used of Israel’s earliest history. But the word qedem is used of God himself on occasion in the OT (Dt 33: 27; Hab 1: 12), of God’s purposes (Isa 37: 26; La 2: 17), of God’s declarations (Isa 45: 21; 46: 10), of the heavens (Ps 68: 33[ 34]), and of the time before creation (Pr 8: 22– 23). At any rate the word qedem can indicate only great antiquity, and its application to a future ruler— one yet to appear on the scene of Israel’s history— is strong evidence that Micah expects a supernatural figure, in keeping with the expectation of Isaiah in 9: 6[ 5], where the future King is called ʾēl (“ God”), an appellation used only of God by Isaiah. This understanding is also in keeping with the common prophetic tradition of God’s eventual rule over the house of Israel (Isa 24: 23; Mic 4: 7; et al.). Only in Christ does this prophecy find fulfillment.

Carroll, M. Daniel; McComiskey, Thomas E.. Hosea, Amos, Micah (The Expositor’s Bible Commentary) (Kindle Locations 7151-7159). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

Another prooftext is John 1:14

14 And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.

The issue with this prooftext is that “only Son” or whether you think it should be “Only-begotten” isn’t sufficient to establish Eternal Generation(See Above). Furthermore, the Son comes from the Father in the sense that he is from the Eternal domain from where the Father, Son, and Spirit reside. Where they are in “face to face” relationship with one another(vs. 1). A theme in this Gospel is from Exodus where God comes down to his people. The Gospel emphasizes that this unique one(The Word) whose glory they saw came ‘from the Father’ into the world (5:36, 37, 43; 6:42, 57; 8:16, 18, 42; 12:49; 13:3; 14:24; 16:28; 17:21, 25; 20:21). He was the one who came ‘from above’ (3:31) and as such was the only one who could make the Father known (18). This is dealing with when Christ was “tabernacling” in the 1st century where they beheld his glory.

Another prooftext John 14:28

“You heard that I said to you, ‘I go away, and I will come to you.’ If you loved Me, you would have rejoiced because I go to the Father, for the Father is greater than I.

We cannot assume that “the Father is greater than I” ipso facto is a statement about ontology. Even proponents of eternal generation recognize this fact. D. A. Carson states it in his commentary:

If the writer of this commentary were to say, ‘Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second is greater than I’, no-one would take this to mean that she is more of a human being than I. The greater than category cannot legitimately be presumed to refer to ontology, apart from the controls imposed by context. The Queen is greater than I in wealth, authority, majesty, influence, renown and doubtless many more ways: only the surrounding discussion could clarify just what type of greatness may be in view.

Carson, D. A.. The Gospel according to John (Pillar New Testament Commentary) (Kindle Locations 10672-10676). Eerdmans Publishing Co – A. Kindle Edition.

He goes on to note that the Father is greater in contrast to the Son being incarnate. That is not the same as saying the Son and Father are distinct because the Son is a derivative of the Father.

The only interpretation that makes adequate sense of the context connects for the Father is greater than I with the main verb (as does the preceding option), but understands the logic of the for or because rather differently: If Jesus’ disciples truly loved him, they would be glad that he is returning to his Father, for he is returning to the sphere where he belongs, to the glory he had with the Father before the world began (17:5), to the place where the Father is undiminished in glory, unquestionably greater than the Son in his incarnate state. To this point the disciples have responded emotionally entirely according to their perception of their own gain or loss. If they had loved Jesus, they would have perceived that his departure to his own ‘home’ was his gain and rejoiced with him at the prospect. As it is, their grief is an index of their self-centredness.

Carson, D. A.. The Gospel according to John (Pillar New Testament Commentary) (Kindle Locations 10688-10694). Eerdmans Publishing Co – A. Kindle Edition.

Another passage that is sometimes brought out is Hebrews 1:3

1 God, having spoken in former times in fragmentary and varied fashion to our forefathers by the prophets, 2 has in these last days spoken to us by a Son whom he appointed to be the heir of everything and through whom he also made the universe. 3 He is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact likeness of his being, and he holds everything together by his powerful word. After he had provided a cleansing from sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Highest Majesty 4 and became as much superior to the angels as the name he has inherited is better than theirs.

The notion that he is the “reflection of God’s glory” is not to say that he is like a mirror image that is caused by the object standing in front of it. But the point is about the fact the Son uniquely reveals the Father. This is connected to the idea that he “the exact likeness of his being”. The fact is, no mere man could do this activity, but rather The Son is divine. I think the Revelational interpretation of passages like this(Col. 1:15-17) fits better than Unitarian or Nicene interpretations.

3. Philosophical arguments:

The most common philosophical argument is that the position leaves only the Son and the Father to share a numerical essence. The Father and Son are identical with nothing distinguishing them. The early Church fathers used eternal generation and procession to distinguish the father from the Son.

The objection fails because the denier of eternal generation is not committed to the claim that the Father and Son have all the same properties. They have the burden to show that they must. It also must be said that Eternal Generation has its own philosophical problems:

But what is this begetting? The idea of begetting, like the idea of sonship, must be refined if it is to refer to God. Among human beings, begetting normally occurs in a sexual relationship. It occurs in time, so that a human being who did not exist at one time exists at a later time by virtue of being begotten. But eternal begetting is surely neither sexual nor temporal, nor, certainly, does it confer existence on someone who otherwise would not have existed; for God is a necessary being, and the three persons share the divine attribute of necessary existence. After we have refined the concept, then, what is left of the idea of eternal begetting? Or should we discard that idea as part of our refining of the term Son? Some have described eternal generation as the “origin” or “cause” of the Son. But that notion poses serious problems. God has no origin or cause; and if the Son is fully God, then he has no origin or cause either. He is a se. He has within himself the complete ground of his existence. Is begetting the cause of the Son in the sense of the divine act that maintains his existence, so that he constantly depends on the Father?704 But this idea would imply that the Son’s existence was contingent, rather than necessary; it, too, would compromise the aseity of the Son.

Most insist that the notion of causality or origin must be distinguished from causes and origins in the finite world: It is not temporal. It is not by the Father’s choice or will, but by his nature. Or it is by his necessary will, rather than his free will. Certainly creation ex nihilo is inappropriate within the Godhead, as the church insisted over against the Arians. But then what is it that eternal generation generates? If eternal generation does not confer existence on the Son, what does it confer? Some claimed that by it the Father communicates to the Son not existence, but the divine nature. Zacharias Ursinus wrote, “The Son is the second person, because the Deity is communicated to him of the Father by eternal generation.” Calvin, however, attacked that position, arguing that “whosoever says that the Son has been given his essence from the Father denies that he has being from himself.”If the Son’s deity is derived, then, says Calvin, the Son is not a se. But if he is not a se, autotheos, “God in himself,” he cannot be divine.

Frame, John M.. Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Christian Belief (Kindle Locations 13626-13646). P&R Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Hays speaks to the issue as well:

So the Son isn’t made in the same sense that the world is made. The Son is coessential and coeternal with the Father. Still, if he owes his existence and essence to the Father, then there’s an unavoidable sense in which the Father made him. That seems to be true by definition, an analytical truth, given the causal dependence of the Son on the Father for his entire substance and subsistence. Within this framework, we might say the Son is an eternal creature or eternal artifact of the Father. We might say the Father communicates his essence to the Son (and Spirit). But the Son is still an artifact of the Father’s action. Father is the producer while the Son is the product. One might try to deny that eternal generation is a causal concept. But if the Father is the source of the Son’s being, then a cause/effect relationship seems to be undeniable. It may not be temporal, but it surely is causal.

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2012/12/begotten-not-made.html

Recommended Reading:

Is God the Son Begotten in His Divine Nature?

See the conquering hero comes!

Eternal Generation and Simplicity

Why is the Spirit the “Spirit”?

For the issues of the Holy Spirit procession and Spiration:

Is the Father greater than the Son?

For the debate on “only begotten”:

3 thoughts on “Is Eternal Generation Biblical?”