I’ll be conducting a series where I review segments of this debate.

https://www.debateart.com/debates/5110-the-bible-is-the-sole-rule-for-all-christian-doctrinal-and-moral-principles

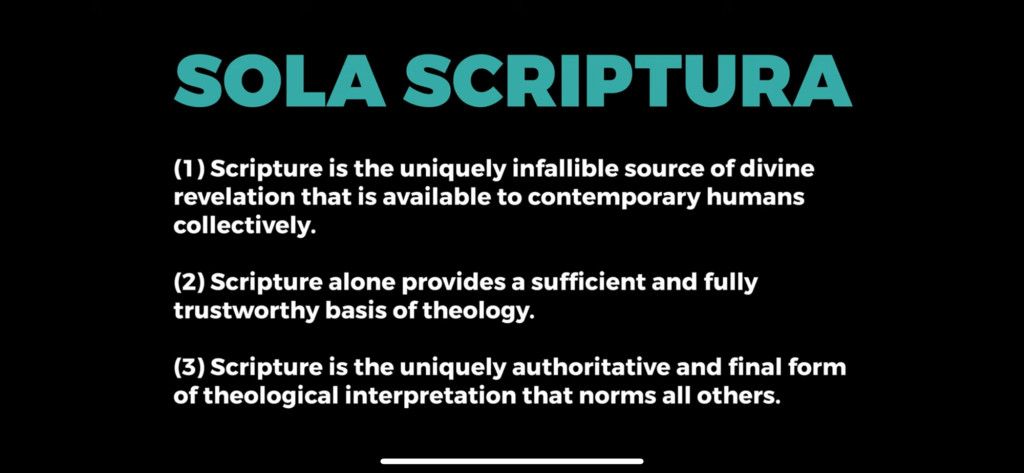

In this debate, I am here to disprove the Protestant notion of sola scriptura: that is, according to the Baptist Confession of 1689:

“The Holy Scripture is the only sufficient, certain, and infallible rule of all saving knowledge, faith, and obedience…”

That Holy Scripture is to be held as authoritative, no Christian can deny without denying their faith. That Holy Scripture is infallible, and thus free from error, I also concede. However, *only sufficient*? I deny – for I hold to that alongside Scripture, there also exists another, extra-biblical authority, called Tradition, which, I will use St. Alphonsus Liguori’s definition of:

“Traditions are those truths which were first communicated by Jesus Christ or by the Holy Ghost to the Apostles, then by the Apostles were given to the disciples, and thus under the guidance of the Holy Ghost without interruption were, so to say, transmitted by hand and communicated up to the present time. These Traditions, which are the unwritten Word of God… are necessary that belief may be given to many articles of Faith…about which nothing at all exists in Scriptures, so that these truths have come to us only in the font of Tradition.”

It consists of:

* doctrines that have been defined and proposed as part of the Faith, such as those concerning the Trinity, the manner of predestination/free will, and the canon of Scripture

* religious practices such as the commemoration of the Last Supper (a.k.a the Mass), or veneration of the saints

* the writings of theologians to explain the interpretation of Scripture, or on the spiritual life

My opponent denies this, and insists that the only rule of faith required is Scripture itself. I will now proceed to show the problems with the sola scriptura thesis from four different viewpoints – a Scriptural, grammatical, logical and historical one.

In my understanding, Sola Scriptura implies that divine revelation serves as the paramount justification for all our knowledge. Only God possesses the all-encompassing perspective needed to reveal the true nature of reality without being hindered by skepticism.

This revelation of God highlights for us the importance of testimony in a Covenantal Epistemology. If we take “testimony” to be that which we believe because someone has told us, then God’s revelation is testimony par excellence. When God says p, it is incumbent upon us to believe p and to take p as true. The problem, as we have said, is that, since the fall into sin, none of us has the “natural” ability to take God at His Word. We have set ourselves against Him and against His truth. So, in that sense, there is a “double testimony” that is necessary for us properly to know. The Westminster Confession puts it this way, “… our full persuasion and assurance of the infallible truth and divine authority thereof, is from the inward work of the Holy Spirit bearing witness by and with the Word in our hearts” (1.5). In other words, what is needed for a credo ut intelligam, Covenantal Epistemology is the testimony of the Scriptures, together with a testimony of the Spirit “by and with the Word” testifying “in our hearts” that the testimony in Scripture is, in fact, the Word of God.

Debating Christian Religious Epistemology . Bloomsbury Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Not all Christians who adhere to Sola Scriptura necessarily align with this perspective, but I contend that they should, hence my presentation in this manner. By distinguishing my distinct positions from theirs, we can discern the correctness of each viewpoint.

Misinterpretations often cloud the understanding of what Sola Scriptura truly involves:

To summarize, sola scriptura is not a

James White – The Roman Catholic Controversy (pg. 59)

1. claim that the Bible contains all knowledge;

2. claim that the Bible is an exhaustive catalog of all religious knowledge;

3. denial of the Church’s authority to teach God’s truth;

4. denial that Cod’s Word has, at times, been spoken;

5. rejection of every kind or use of tradition;

6. denial of the role of the Holy Spirit in guiding the Church.

The concept of tradition within Catholicism raises pertinent questions: What constitutes tradition? What is its origin, and how did the earliest Church perceive tradition? Defining this notion often poses a challenge for Catholics. James White highlights the complexity by outlining two of the most expansive views from the Council of Trent.

Despite the fact that the preceding citations seem rather clear, as with any written communication there are differences of understanding expressed within the broad spectrum that makes up Roman Catholicism. In fact, the two primary positions set forth regarding the nature, extent, and authority of tradition are, logically speaking, mutually exclusive. Yet they exist side by side in Roman Catholic theology. One of the great ironies of this entire conflict is that while Rome claims ultimate authority in teaching and interpretation of divine truths, and while her defenders constantly point to the “doctrinal chaos” that exists in denominations that hold to sola scriptura, she allows her followers to hold to perspectives completely at odds with each other on points as basic as the extent and authority of tradition itself. …

Roman theology speaks with two voices concerning the concept of the sufficiency or insufficiency of Scripture. The older and, I believe, far louder voice advocates the traditional concept of two “modes” or “sources” of revelation: Scripture and oral tradition. In this concept the oral traditions actually exist; that is, there are oral traditions that were passed on to the successors of the Apostles long ago. These traditions have been guarded and passed down through the episcopate to this day. The term “Apostolic tradition” has meaning in this viewpoint, as it is believed that there is a real substance, a real existence, to these traditions. They are identifiable things that existed in history. This perspective is expressed clearly in the first draft of the decree on the Scriptures issued by the Council of Trent, which said that revelation is passed on “partly in written books, partly in unwritten traditions.” This viewpoint, which we will call the partim-partim view (partim being Latin for “partly”), teaches that part of God’s revelation is found in Scripture, but not all of it, and part of God’s revelation is found in the oral traditions, but not all of it. In order to have all that God intends you to have, you must have both. …

The second viewpoint put forth by Roman Catholics does not have to deal with this kind of historic criticism, since it is not nearly as bold in its claims. Instead, it affirms the material sufficiency of the Bible. These theologians assert that divine revelation is contained entirely in Scripture and entirely in tradition, totum in Scriptura, totum in traditione. It is vital to immediately point out that these Roman Catholic theologians are not affirming sola scriptura. Instead, they are saying that all of divine revelation can be found, if only implicitly, in Scripture. That means that such doctrines as the Immaculate Conception, the Bodily Assumption of Mary, and Papal Infallibility are, from this perspective, implicitly found in Scripture.

James White – The Roman Catholic Controversy (pg. 76-78)

Newman’s theory of doctrinal development diverges from traditional stances on Divine revelation’s transmission, signaling what many might view as problematic. It surpasses the belief that every teaching stems solely from an oral tradition perpetuated by the Church (partim-partim) and extends beyond the notion that Scripture alone contains all Divine revelation implicitly (material sufficiency).

However, Newman’s nuanced perspective might be seen as concerning: it suggests that Divine revelation progressively unfolds within the ongoing life of the Church. This view implies that the complete depth of truth isn’t distinctly present in the earliest teachings or confined within Scripture. Instead, it allows for the notion that the understanding of Divine truths evolves over time, potentially raising doubts about the completeness or clarity of original revelations.

The early Christian Church was characterized by its emphasis on public attestations of tradition, a critical response to the secretive, often esoteric traditions claimed by Gnostic groups. This public nature of apostolic traditions was pivotal in distinguishing the orthodox Christian teachings from Gnostic heresies, which often relied on hidden knowledge accessible only to a select few. As the Church evolved from a predominantly oral culture to one more reliant on written scriptures and formal doctrines, the manner in which traditions were maintained and transmitted also transformed, leading to varying interpretations of their authority and scope within the broader Christian community. This historical journey from the early Church’s public and verifiable traditions to the more developed and nuanced views of tradition in contemporary Catholic theology illustrates the complex evolution in the handling and perception of tradition. This evolution is critical to understanding the current debates on the sufficiency of Scripture and tradition in Catholic theology, shedding light on the dynamic and evolving nature of doctrinal development within the Church.

This framework, while honoring Scripture and tradition, implies that Divine revelation undergoes a continuous process of growth and adaptation.

The ongoing evolution of perspectives on tradition within the Catholic Church has surpassed Newman’s era. Prominent theologians like Hans Küng, Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), Oscar Cullmann, and Karl Rahner have critically examined and questioned Newman’s principles governing valid doctrinal development.

In summary, the Catholic apologist skillfully argues against a limited interpretation of Sola Scriptura—a mere confessional perspective. However, this critique falls short as it overlooks broader variants like mine, which embrace a Covenantal epistemological stance. Additionally, there’s a lack of clarity regarding his own view of tradition, hindering a thorough rebuttal from his opponent.

Critiquing the Catholic View of Tradition: A Protestant Perspective

The Roman Catholic Church’s understanding of tradition, especially as formalized during the Council of Trent, presents a significant point of divergence from Protestant theology. This critique seeks to address the Catholic view of tradition by examining its foundations, theological implications, and historical consistency.

The Foundation of Catholic Tradition

The Catholic Church posits that tradition, alongside Scripture, constitutes a dual source of divine revelation. This view was robustly articulated at the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which declared that the truths necessary for salvation are contained both in the written books (Scripture) and in the unwritten traditions that have been handed down. These traditions, according to Trent, are to be received with equal reverence as the Scriptures themselves.

One pivotal decree from Trent states:

“In addition, the same holy Synod… ordains and declares that the same ancient Vulgate edition… is to be considered as authentic, and that no one is to dare or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever. (Council of Trent, Session IV, 1546)”

This decree not only affirmed Jerome’s Latin Vulgate as the authoritative text but also underscored the broader Catholic assertion that tradition holds an authority equal to that of Scripture.

Theological Implications

The Catholic view of tradition raises several theological concerns:

Insufficiency of Scripture: By asserting that unwritten traditions are equally authoritative, the Catholic Church implies that Scripture alone is insufficient. This stands in contrast to the Protestant principle of sola scriptura, which holds that Scripture is the sole infallible rule of faith and practice. Protestants argue that Scripture is God-breathed (2 Timothy 3:16) and thoroughly equips believers for every good work, suggesting its sufficiency.

Obscurity of Scripture: The Catholic Church often argues that Scripture is too obscure and ambiguous to be understood without the guiding framework of tradition. This view is seen to undermine the clarity or perspicuity of Scripture. Protestant theology contends that while some passages are challenging, the core message of Scripture regarding salvation and essential doctrines is clear and accessible to all believers (Psalm 119:105).

Authority and Interpretation: The Catholic Church claims that it alone has the authority to authentically interpret Scripture. This is problematic from a Protestant standpoint because it can lead to an elevation of the Church’s interpretive authority above Scripture itself, potentially leading to doctrines that cannot be substantiated by the biblical text.

Historical Consistency

A critical examination of the historical development of Catholic tradition reveals inconsistencies that challenge its claims of an unbroken apostolic transmission:

The Pharisaic Parallel: Similar to the Pharisees’ traditions in Jesus’ time, which were claimed to be handed down from Moses but often contradicted the written Law, Catholic traditions are critiqued for lacking clear biblical support. Jesus rebuked the Pharisees for allowing their traditions to nullify the word of God (Mark 7:13).

Doctrinal Developments: The Catholic Church’s reliance on tradition has led to the development of doctrines that are not explicitly found in Scripture, such as the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of Mary. These teachings, declared dogmatically in the 19th and 20th centuries respectively, raise questions about their apostolic origins and the criteria by which they were deemed necessary for belief.

The Issue of the Vulgate: The Council of Trent’s declaration of Jerome’s Latin Vulgate as the sole authentic text poses historical and textual criticism issues. The Vulgate contains translations that have been shown to differ from the earliest Greek manuscripts, such as the translation of “repentance” as “do penance” (Matthew 3:2, “paenitentiam agite”). This has significant theological implications, especially regarding the understanding of repentance and justification.

Categories of Tradition

From the text, the different usages of tradition can be categorized and understood as follows:

- Oral Tradition Later Written Down: This refers to the teachings and practices initially transmitted orally by Jesus and the apostles, which were later documented in the New Testament scriptures. This is often seen as the primary form of tradition that Protestants accept as authoritative.

- Tradition as Authority for Scripture Canon: This tradition involves the role of the early church in recognizing and transmitting the canonical books of the Bible. It’s the tradition that determined the New Testament canon and is accepted reverently as an essential part of church history, helping to identify which books are considered inspired.

- Apostolic Tradition in the Early Church: This encompasses the teachings and practices handed down directly from the apostles, which were used by early church fathers like Irenaeus and Tertullian to combat heresies such as Gnosticism. These traditions are often seen as consistent with the teachings found in scripture and include elements like the Apostles’ Creed.

- Tradition as a Catch-All for Unwritten Doctrines: This is the Roman Catholic view criticized by Chemnitz, where tradition includes teachings and practices not explicitly found in scripture but believed to have been handed down orally through the church’s magisterium. Examples cited include doctrines like the bodily assumption of Mary or indulgences, which are argued to lack clear scriptural basis.

- Tradition in Patristic Writings: The way early church fathers like Irenaeus and Tertullian referred to tradition often meant the public, universally acknowledged teachings of the apostles, which were consistent with scripture and not secret or additional doctrines.

- Development of Doctrine: This modern Roman Catholic perspective, associated with John Henry Newman’s theory, suggests that church doctrines can develop over time, and tradition includes these developments. This view is contrasted with the stance during the Reformation, where the Roman Catholic argument was that existing doctrines and practices had been consistent since the apostolic era.

- Tradition in Opposition to Gnosticism: This specific use of tradition was employed by early church fathers to refute Gnostic claims by appealing to the publicly known and transmitted teachings of the apostles, as opposed to secret traditions claimed by Gnostics.

- Tradition as Defined by the Papacy: According to Chemnitz, this is the tradition that the Roman Catholic Church uses to justify practices and dogmas not found in scripture, asserting that the magisterium has the authority to determine and transmit these traditions.

The Inconsistency between Newman and Trent

The Council of Trent and John Henry Newman’s views on tradition and doctrinal development present notable inconsistencies. Trent asserted a static view of tradition, where divine revelation is contained “partly in written books, partly in unwritten traditions,” suggesting that the full deposit of faith was given once and for all to the apostles and passed down unchanged.

Newman, however, proposed a dynamic understanding through his theory of doctrinal development, suggesting that doctrines can evolve and mature over time as the Church deepens its understanding. This implies that certain doctrines may not have been fully explicit in the apostolic era but have developed in clarity and detail through the Church’s historical and theological reflection.

Council of Trent on Tradition

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was clear in its decree that both Scripture and unwritten traditions were to be received with equal reverence:

“The Council clearly perceives that this truth and rule are contained in the written books and the unwritten traditions which, received by the apostles from the mouth of Christ himself, or from the apostles themselves, the Holy Ghost dictating, have come down even unto us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand.” (Council of Trent, Session IV, 1546)

This statement indicates a belief in the fixed and complete nature of apostolic tradition, where all necessary teachings were handed down once and directly from Christ and the apostles.

Newman’s Theory of Doctrinal Development

John Henry Newman, in his 1845 essay “An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine,” argued for a more organic view of tradition. He suggested that doctrine can develop and become more explicit over time:

“It becomes stronger, more substantial, and more defined, by the action of the mind upon it, and thus issues in the Church as a definite and complete dogma.”

Newman’s approach allows for a historical and progressive unfolding of doctrinal understanding, which stands in contrast to Trent’s more static and immediate transmission of all necessary truths.

Points of Inconsistency

- Static vs. Dynamic Tradition: Trent’s view implies that all doctrinal content was fully present and explicit from the beginning, whereas Newman’s theory allows for growth and development in understanding over time.

- Authority of Tradition: Trent holds that both Scripture and unwritten traditions from the apostles are equally authoritative and unchanging. Newman’s view can be interpreted as suggesting that the Church’s understanding of these traditions can grow and become clearer over time, potentially implying that some doctrines were not fully articulated in the early Church.

- Interpretation of Revelation: Trent asserts that the full deposit of faith was handed down completely and directly, whereas Newman sees this deposit as something that can develop as the Church reflects on and interprets it over centuries.

Misinterpretation of Key Biblical Texts

Jeremiah 31:33

Text: “But this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people.”

Roman Catholic Use: The Catholic Church uses this verse to argue that the law of God and the teachings of Christ are inscribed on the hearts of believers, suggesting that not all divine revelation is contained solely in written scripture but also in the living tradition and internal witness.

Chemnitz’s Interpretation: Chemnitz argues that this passage refers to the internal transformation by the Holy Spirit, emphasizing that God’s law becomes an integral part of the believer’s nature through regeneration. He insists that this does not support an unwritten tradition but instead highlights the transformative power of God’s Word as internalized by the believer.

Chemnitz’s Critique: “And the fathers are not ignorant that when God wanted the sum of his will to be set forth and committed to writing, he ordered Moses and the prophets: ‘Write down what I command you,’ Ex. 34:27; Is. 8:1, 30:8; Jer. 30:2. And it is very well known what Jerome, in his preface to his commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, relates concerning the fifty Hebrew volumes which the Jews falsely assert to have been hidden, the contents of which, they claim, are more extensive than those of the canonical books” (Chemnitz, Examination of the Council of Trent, Part 1, p. 524).

2 Corinthians 3:3

Text: “And you show that you are a letter from Christ delivered by us, written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts.”

Roman Catholic Use: The Catholic interpretation often uses this verse to demonstrate that the Holy Spirit inscribes God’s law and teachings directly onto believers’ hearts, reinforcing the idea that divine truths are also conveyed through oral tradition and the Church’s magisterium, not merely through written texts.

Chemnitz’s Interpretation: Chemnitz contends that this verse is about the Spirit’s work in believers’ hearts, producing a living testimony of Christ’s teachings. He argues that Paul is not suggesting an alternative source of divine authority outside of scripture but is instead speaking about the personal and transformative nature of the Spirit’s work in making believers living testimonies of Christ’s teachings.

Chemnitz’s Critique: “For the Spirit is therefore called ‘the seal’ because he impresses the image of Christ on the hearts of believers, so that the same Christ may live in the believer, and the believer in Christ. Nor does the Spirit give any other image or other content than that which is given in the written Word, as Paul clearly indicates when he says, Rom. 10:8: ‘The Word is near you, on your lips and in your heart.’ Thus, the Word is written inwardly by the Spirit” (Chemnitz, Examination of the Council of Trent, Part 1, p. 82).

For more, check out these articles:

2 thoughts on “The Battle of Doctrinal Foundations: Examining Sola Scriptura and Tradition”