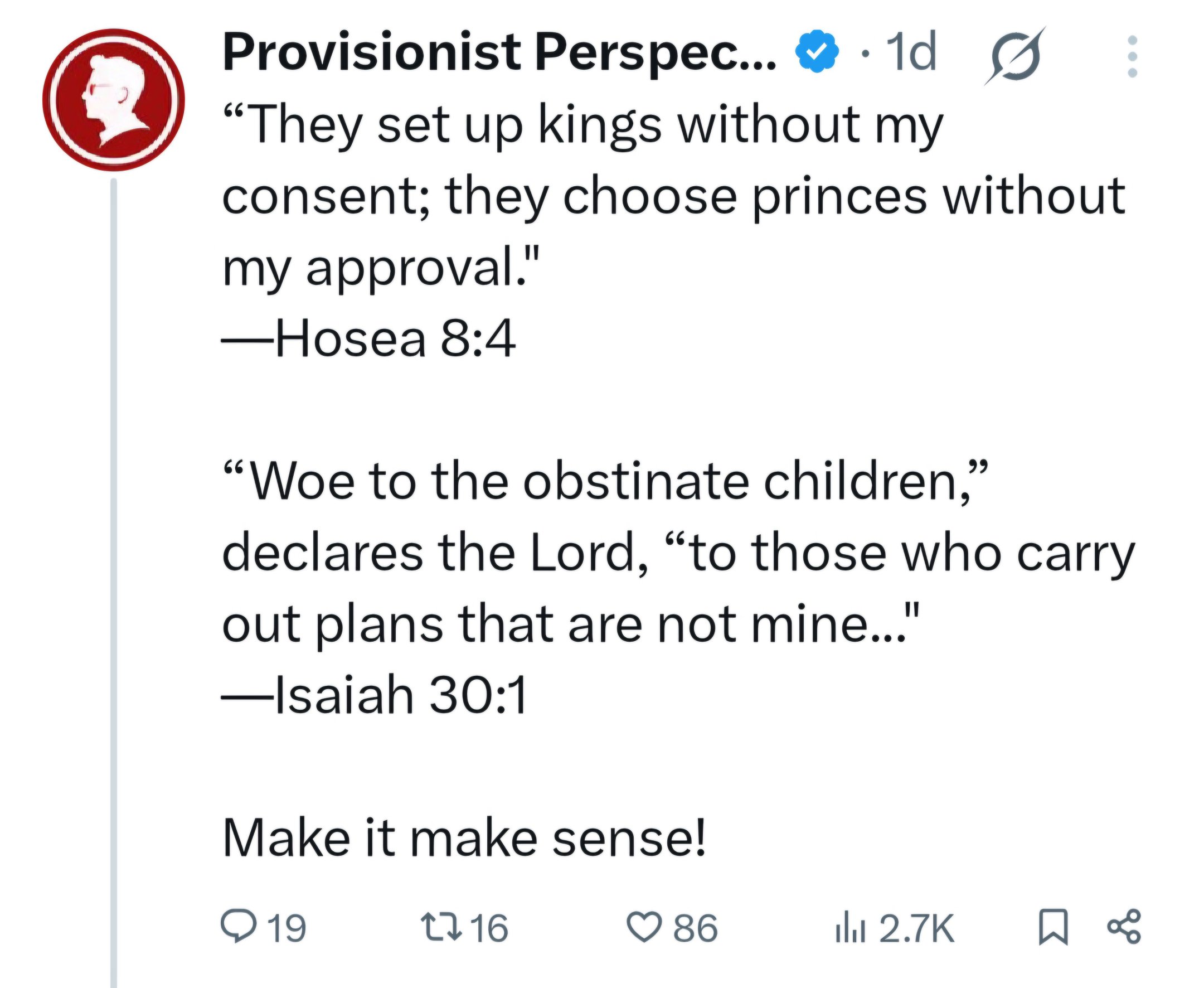

A popular anti-Calvinist tweet recently circulated, citing Hosea 8:4 (“They set up kings without my consent”) and Isaiah 30:1 (“They carry out plans—but not mine”) as supposed proof that some human actions fall outside of God’s will. The argument goes something like this: If God says He didn’t plan something, then clearly He didn’t decree it—therefore, Calvinism is false.

At first glance, this might sound like a slam dunk against the Reformed view of meticulous providence. But on closer inspection, this argument collapses—not just as a critique of Calvinism, but as a coherent theological claim at all. In fact, when taken seriously, it ends up affirming the basic tenets of open theism, not Provisionism. That’s a problem, because even many of Calvinism’s critics (like Leighton Flowers) reject open theism.

Let’s walk through the issues.

I. The Category Error: Moral Disapproval ≠ Causal Power

The foundational mistake in this kind of argument is the conflation of two distinct categories:

- God’s moral will (what He commands and approves),

- God’s sovereign will (what He ordains and brings to pass).

When God says, “They carry out plans that are not mine,” He isn’t claiming to lack power or foresight. He is expressing displeasure at rebellion. This is not a denial of sovereignty—it is a statement of judgment.

Reformed theology has always maintained this distinction. God can ordain that an evil act occur without approving of the evil itself. That’s how we can say things like:

- The crucifixion was predestined by God (Acts 2:23; 4:27–28), and yet those who carried it out were guilty of murder.

- Joseph’s betrayal was meant for evil by his brothers, but “God meant it for good” (Gen. 50:20).

These acts were evil and against God’s moral will, but they were not outside His control or eternal plan. While Provisionists offer rejoinders to Genesis 50, that’s beside the point here. The goal is not to defend a specific interpretation, but to highlight the kind of category distinction they themselves implicitly rely on elsewhere.

II. What These Verses Actually Mean

Let’s consider the specific verses being used as weapons against Calvinism:

- Hosea 8:4 – “They set up kings without my consent” is not a metaphysical statement about God’s sovereignty; it’s a moral indictment. It condemns Israel’s rebellion in establishing rulers contrary to God’s law—possibly in the Northern Kingdom after the division from Judah. But just like in 1 Samuel 8, where Israel demanded a king and God said, “They have rejected me from being king over them,” He still granted their request as part of His broader plan. It was evil, but it wasn’t outside His will in the ultimate sense.

- Isaiah 30:1 – “They carry out a plan, but not mine” refers to Israel’s alliance with Egypt—a decision that reflects their lack of trust in Yahweh. It was a political alliance that reflected spiritual adultery. But this sin was still used by God to chasten His people, provoke judgment, and ultimately bring about restoration. The plan was “not His” in terms of moral approval—not divine oversight.

In both texts, God’s displeasure is on display—but not divine impotence. These are covenantal rebukes, not metaphysical disclaimers. And ironically, the broader context of Isaiah repeatedly affirms God’s meticulous planning over all things.

III. Even Leighton Flowers Thinks God Plans the Cross

The irony here is that even prominent Provisionists affirm the very distinction they claim undermines Calvinism. Dr. Leighton Flowers, for instance, repeatedly describes God’s orchestration of the cross using the analogy of a police sting operation:

“Appealing to God’s sovereign work to ensure the redemption of sin so as to prove that God sovereignly works to bring about all the sin that was redeemed is an absurd, self-defeating argument. It would be tantamount to arguing that because a police department set up a sting operation to catch a notorious drug dealer, that the police department is responsible for every single intention and action of all drug dealers at all times.” —Leighton Flowers, What You Meant For Evil, God Meant For Good

“Teaching that God brings about all sin based on how He brought about Calvary is like teaching that the police officer brings about every drug deal based on how he brought about one sting operation.” —Leighton Flowers, Does Calvary Prove Divine Determinism?

But notice: Flowers still affirms that God planned the crucifixion. He just denies that this means God planned all sin in the same way. Yet in making that move, he’s admitting the core idea Calvinists affirm: God can plan evil events without morally approving of them.

That’s the very distinction Hosea 8:4 and Isaiah 30:1 require—a distinction the Provisionist perspective often denies.

IV. What This Argument Really Proves: Open Theism

The real implication of this argument is not anti-Calvinism. It’s open theism.

If God’s disapproval of something entails that He had no part in causally ordaining it or that His plan wouldn’t include it, then God doesn’t have a comprehensive plan for history. He’s reacting to human choices, not ruling over them. He is surprised, disappointed, and scrambling to adjust to human rebellion.

Ironically, most Provisionists would reject this conclusion. They want to say God permits evil for good reasons, that He plans certain outcomes without approving of the sin involved. But once you grant that, you’ve already dismantled the objection from Hosea 8:4 and Isaiah 30:1.

V. Open Theism’s Intelligence Problem

Even if someone were to bite the bullet and say these verses show God didn’t plan the events described, the problem doesn’t go away—it just shifts. Because even in open theism, God is supposed to have perfect knowledge of the present and some ability to predict the future based on the current trajectory of events.

But that raises an uncomfortable question:

If God can’t anticipate what a group of kings or rebels are going to do—even after months of observation and knowing their internal thoughts—why believe He can ever reliably predict anything?

Was Israel’s rebellion so complex, so sudden, so multilayered, that even the all-wise Creator couldn’t forecast it? Was it really too hard for God to anticipate that dozens of agents acting in rebellion might form an alliance or set up kings? If so, what exactly can God predict in the open theist model?

The answer is: not much. And if that’s the case, then not even open theism can sustain a meaningful doctrine of prophecy, providence, or long-term divine planning. Once you go down this road, you don’t just lose Calvinism—you lose the Bible.

But here’s the deeper problem: What justifies divine negligence? If God could have foreseen the sin, could have warned, could have intervened—and didn’t—then what grounds do open theists have for trusting such a God at all? What if He fails again? What if the next move surprises Him too?

This isn’t just about philosophical coherence—it’s about theological confidence. A God who can’t guarantee the future and lets catastrophe unfold without plan or purpose is not a God worthy of trust. He is, at best, negligent—and at worst, complicit in evil without any redemptive aim.

VI. Providence Isn’t Deception: A Final Word

Another objection, from Dr. Theologician, raised in response to the Reformed view is this: “It makes no sense that God would present reality one way while secretly doing something else. It’s unlivable and disingenuous.”

This objection collapses once you recognize the difference between God’s causal powers and His commands. These are not the same kinds of facts. What God causes is not what He commands. The moral law and the sovereign decree operate on different planes. God doesn’t intend His providence to serve as a moral prescription. So it’s not disingenuous. Deception requires intent to mislead.

That’s why I often compare this to a glass door. Just because you walk into it doesn’t mean the designer tricked you. The glass was never pretending to be open air. If you mistook it for something it wasn’t, the fault lies in your assumptions, not the architect. The same goes for reading providence as if it were a revelation of moral norms.

In Scripture, God frequently brings about what He morally disapproves:

- Pharaoh is told to let Israel go, and yet God hardens his heart.

- Judas is condemned for his betrayal, and yet it was predestined.

- Jesus weeps over Jerusalem, and yet its destruction was decreed.

- The Jews were hardened, and yet commanded to repent.

These aren’t contradictions. They’re revelations of divine majesty. God brings about what He hates in order to accomplish what He loves.

The open theist wants to say God can override outcomes when it suits a redemptive end, but then turns around and cites cases like Hosea 8:4 and Isaiah 30:1 where God supposedly fails to do so. Which is it? Does God fail sometimes? Or does His nature conveniently shift to fit the argument?

VII. Underdetermination

On Scott Oliphint’s model of God, it is entirely consistent to affirm that God may change His mind or adjust His plans—not in His eternal essence, but in accordance with His covenantal properties. Just as the incarnation involved God taking on a new relation to creation without altering His divine nature, so too God may engage with history in dynamic ways while still maintaining a comprehensive, sovereign plan.

Thus, even if Hosea 8:4 or Isaiah 30:1 were interpreted as examples of divine change, they would not prove open theism. At most, they would support a view in which God temporally responds to covenantal violations while still upholding an immutable decree. In other words, these verses are equally—if not more—at home in a Reformed framework than in any open theist model.

No prooftext from these passages justifies the theological overhaul that open theism demands.

Conclusion

God’s sovereign decrees and moral commands are not the same thing, and no biblical author thought they were. If your theology can’t hold that together, it’s not more biblical—it’s just smaller.

In the end, the critique that “God is being disingenuous” tells us more about modern assumptions than it does about Scripture. The biblical God governs all things wisely—even when we don’t understand how.

One thought on “Not His Plan? A Reformed Response to a Common Prooftext Error”